Ok, obviously not all of that is play time. I’m in graduate school, and none of my seminar projects are about Wingspan, so this isn’t something I do for hours on end. But…I did convince half of my family to get the game and have bought it for every relative’s birthday so far…so we’ve become a bit of a bird clan. We have a half dozen games going on at any one time since players can take up to 24 hours between turns.

But mainly, Wingspan became a soothing social background process. The keyword is soothing. Certainly, the soundtrack is beautiful, but interestingly, the sound settings themselves helped Wingspan replace my carefully curated YouTube library of music compilations and ambient rooms.

There’s a lot of sound going on in a game of Wingspan.

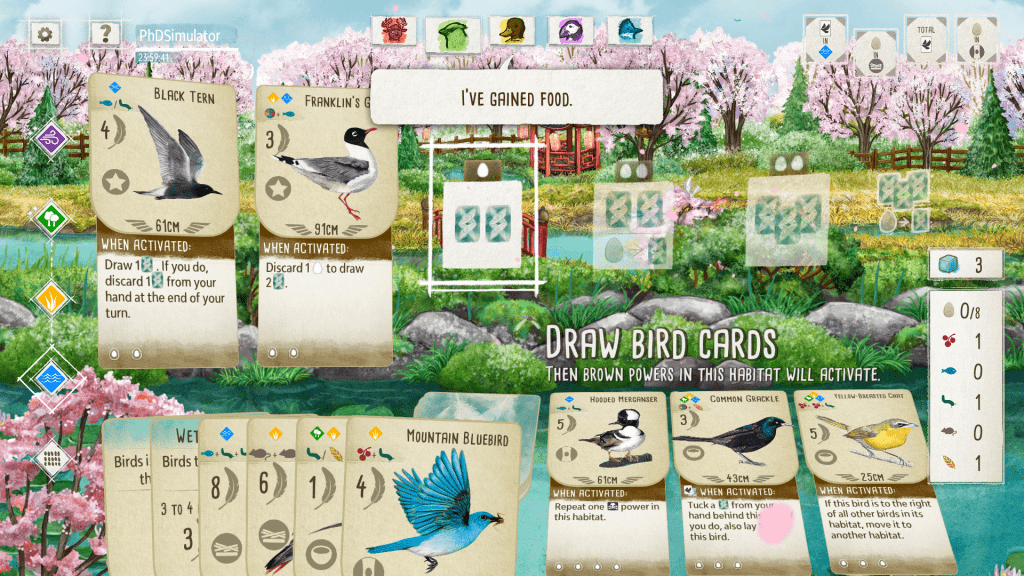

Each bird played sings when clicked on or activated in a turn, but their songs are also integrated into the ambient sounds of the aviary (here I’m referring to sounds that play without player interaction as ambient). Another layer of sound is the background songs of ambient birds—bird songs that aren’t from played birds—and the music itself. That might sound like a cacophony, but for two simple reasons, it facilitates a soothing play experience that is malleable in that it can move with me throughout my day:

- It’s well mixed; bird songs vary, making the overall audio output well-balanced and more “realistic” than common bird sounds videos available on YouTube or on that one CD rack at every Bed Bath and Beyond (does that thing still have cassettes?).

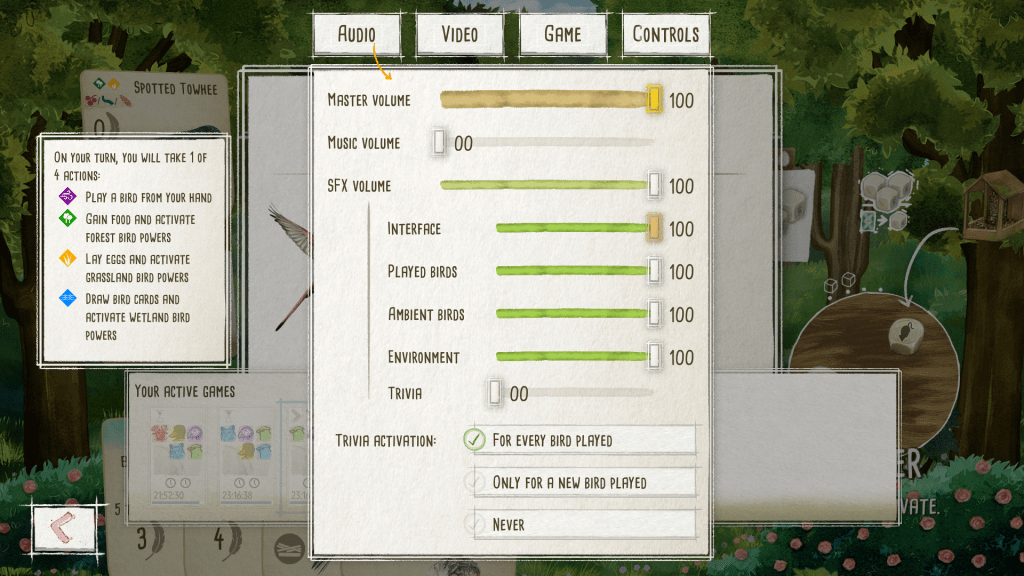

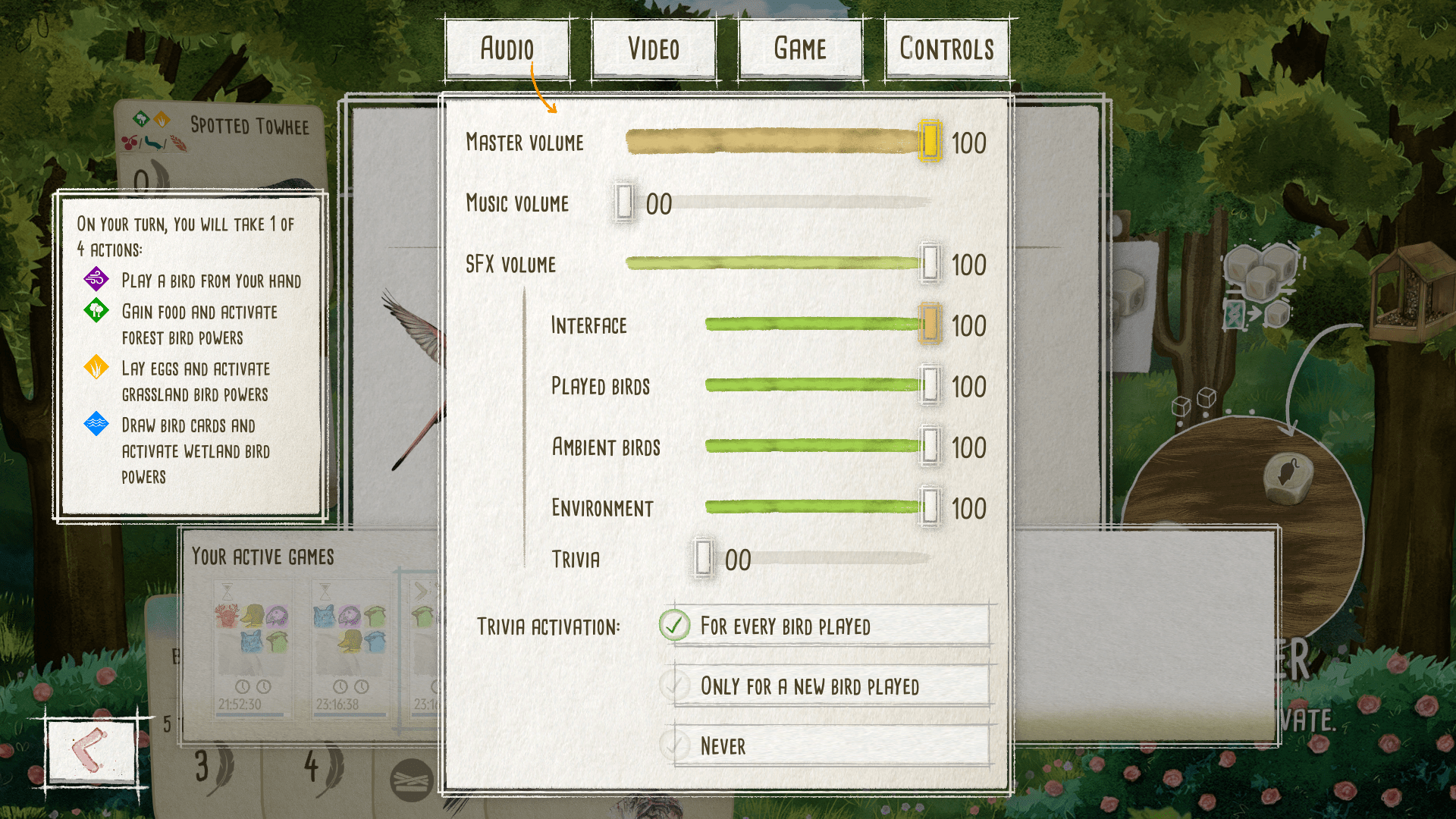

- Players have control over each layer of audio. This one has proven key for Wingspan becoming a work companion because the game space becomes a cheerful extension of my workspace.

Audio menu for Wingspan. Players have control over the music and sound effects in the game. Sound effects are broken up into the interface (scrolling menus, turn notifications, click-responses), played birds (songs/sounds by birds played in the game), ambient birds (general background of birdsongs), environment (whooshing air, softly rustling sounds), and trivia (trivia narrator’s voice volume).

There are a million and one things that can be said about this game in both its digital and analog form. But today, I’m especially interested in what all these layers of sound, and the ability to manipulate the way those layers work together, lends Wingspan to the kind of game that can be anything between a soothing background process like I described and a competitive game that commands full attention. In both these forms and in between, the game remains compelling. What’s up with that? For me, the affordance of audio control makes all the difference.

As I was writing this post, I played a few live rounds of the game with each kind of audio on full blast, and the others muted. So, with Environment at 100, all the others were at 0. Until I did this, I wasn’t sure what the environment sound even was because it’s so subtle and only makes a tangible difference in conjunction with other sounds. Even at full volume, this is somewhat indiscernible in isolation and only carries meaning when looking at the game screen. With the environment sound at full volume in between turns, players can review their boards and played cards overlaid an environment background of their choice. With trees swaying in the background, the previously indiscernible noise becomes soft, distant leaves rustling in a breeze a few yards away. Adding in the sounds of ambient birds places the player more solidly in a natural landscape, even with the game screen operating in the background behind a browser or word processing window.

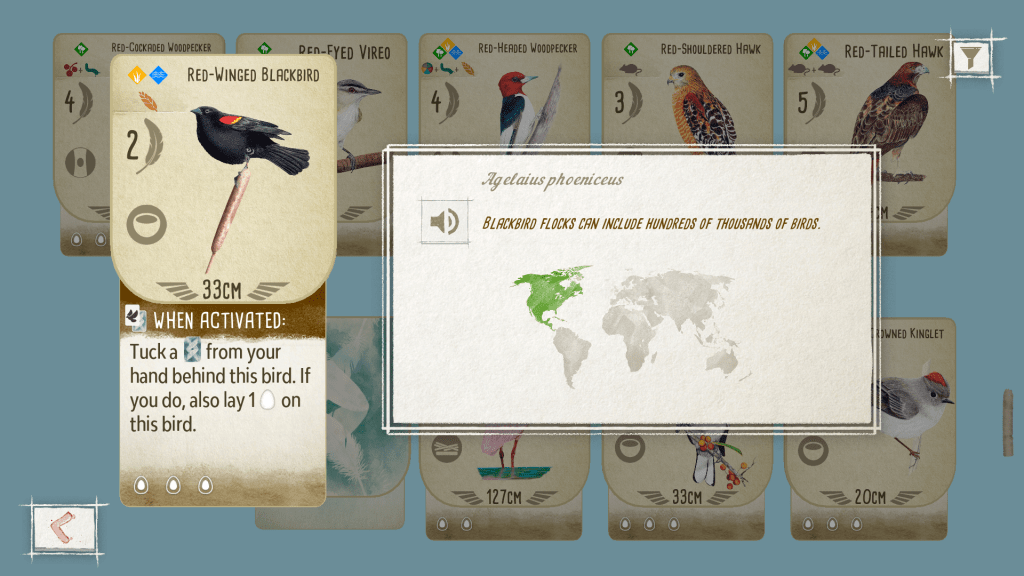

The realism, however, gains concreteness because of the “played birds” sounds. This category specifically refers to the birds that the player(s) have put out on the board, the combination of which is wildly different from game to game. This blend is largely random; no one bird tends to be privileged over another in its song, lending a sense of audio realism to the digital game’s spatial narrative that players are volunteering as workers in a wilderness preserve. The birds whose songs players hear live in that space, sharing that room with the player. The occasional growling snort of a turkey vulture has shocked me out of writing a sentence, just as the sharp trilling of a red-winged blackbird played so often that I’ve learned to identify it when I’m outdoors.

In this way, my relatives and I share digital birding knowledge, each of us spending the day with the song-filled spaces of our making and design as we go about our work. For example, when I’m writing away from my computer, I change the game’s audio settings to only signal when I have a new turn (interface at 100, everything else at 0) so I’ll hear it elsewhere and know the game has passed to me. The option to adapt the game’s sounds to what I’m doing—especially the ability to mute the music and amp up the birds themselves—renders the game an object that moves with me as I work through and transition between tasks and headspaces. This certainly comes in part from my personal relationship with nature, cultivated on the shores of Gitchigami during graduate school, but the seamlessness I’m describing here isn’t limited to someone who prefers the outdoors. Rather, affording the player the control of adjusting the game’s sounds with such specificity allows the player to mold their perception of the game’s environment to their own environment beyond the screen.

Something interesting about sound is how it assists in the perception of a space, like the hollow echos of Inside the Deku Tree. Making those sounds customizable has become a staple of modern gaming, and I wonder how that could potentially change the relationship between player and text? This also reminds me of an interesting article I saw during my research about the game Inside, which talks about audio looping and puzzle solving. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40869-018-0071-x

Great post, Janelle! I think the audio was the first thing I noticed about the game the first time I caught ya’ll playing it on Board Meeting. I can’t help but to compare in my mind the way you describe this game to some combination of “Kind Words (lofi chill beats to write to)” and maybe “Mountain”.