Hi everyone!

I’m thinking about writing about the link between the game Inside and abjection for a course, so I thought I’d take some time to write down my thoughts here.

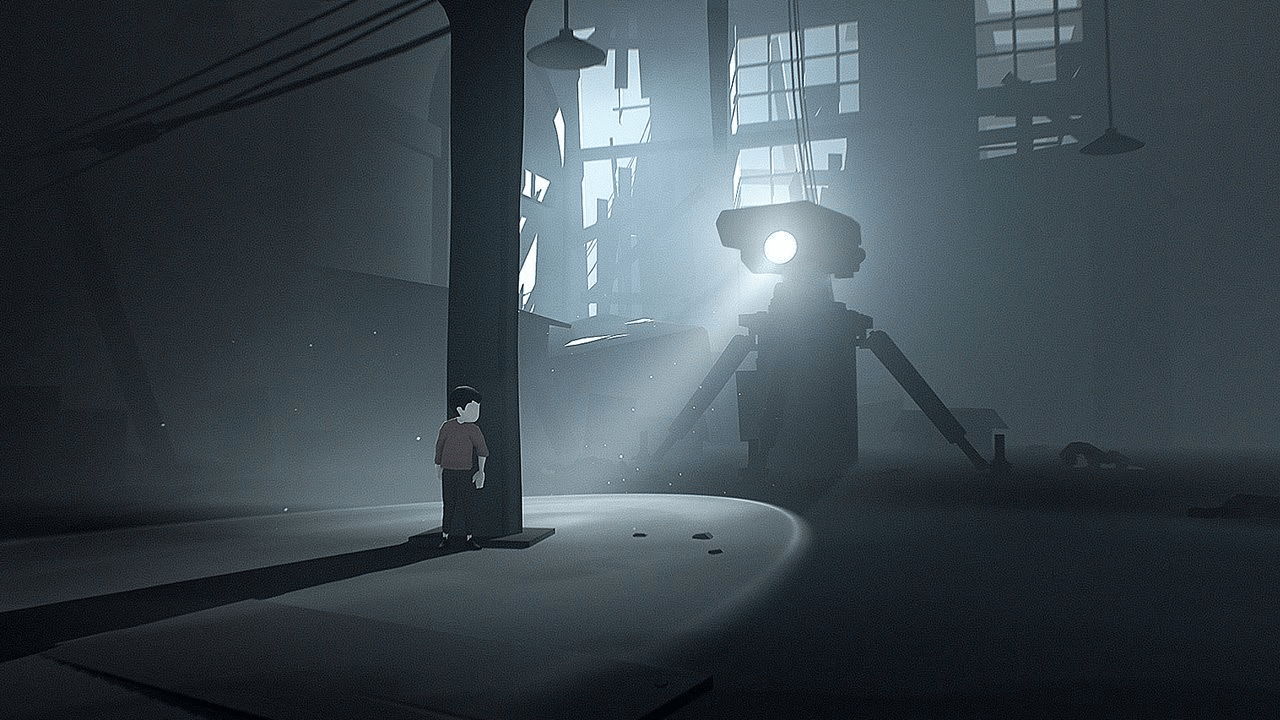

The player of Inside (2016) controls a nameless, faceless character, coded as a boy, that has a nameless, faceless mission. There’s no overt narrative to the game, meaning the only storytelling in the game is environmental and/or visual in some way. For example, near the beginning of the game, your character is followed by a number of trucks full of adversaries who shoot you on sight if they see you, but you never really understand why they’re hunting you down. These shooters are implied to be linked to the leaders of a large factory and laboratory seen later in the game, but even then this relationship is tenuous and never fully explained.

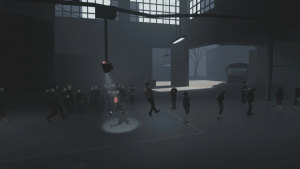

As the game continues, more and more strange, unsettling, and parasitic events occur. To stop a pig from mauling the avatar to death, the player-character must pull a parasitic worm out of its rear. The avatar uses an old-fashioned helmet-like device to control the lifeless bodies of other people to solve puzzles. In one particularly harrowing moment, the avatar must pretend to be one of the lifeless drones that are being inspected at the factory. The player-character must jump, turn around, and walk in line at the same pace as the other characters in order to pass the inspection and continue their journey.

At the end, the avatar, either willingly or unknowingly, infiltrates the inner depths of the lab and imbues himself in a mass of flesh and wriggling limbs. The player controls this behemoth for the rest of the game, destroying large portions of the lab and eventually escaping into the sunlight, the only time a genuinely warm glow appear in the game. Like with everything else in the game, nothing is ever explained directly to the player. What is this mass of flesh? Why did the avatar become part of it? Did he mean to? Why was this mass of humans produced in the first place?

As Emma Reay points out, there are a loooot of secrets and just a general sense of confusion that permeates the game. Reay argues that Inside’s story is confused even further when the player, assuming the adult position of control over the child-character, is bamboozled by the will of the child-character, whose ultimate goal is to assist in the destruction of the factory, something we in the role of the adult-player never really see coming.

I would argue that while this is true, the power in the child-character and adult-player relationships is blurred more than it is inverted. After all, the player continues to control the massive blob that the child themselves becomes a part of. The game also never truly reveals whether the child means to become a part of the blob. In the scene in which the child attempts to free the blob, we see the child-character resist being pulled into the blob. So what is the true motive of the child? And what’s the true motive of us, the player?

I’d argue this confusion, along with the host of uncanny, parasitic, and body horror elements in the game, ties closely with Julia Kristeva’s conceptualization of abjection. For Kristeva, the abject is anything that resides within the liminality of Symbolic Order, which is the ordering power of symbolic language, particularly seen within in binary oppositions like legal/illegal, good/evil, pure/impure. Lacan equates the Symbolic Order with Law and paternal authority.

In Inside, I would argue the main binary it deconstructs is the being/non-being, a distinction which humans have constructed to position themselves as the center of universal meaning and articulation. In essence, we humans get to determine what is “real,” “lawful,” and “right” because we are beings capable of reasonable thought, while non-beings (most animals and inanimate objects) don’t have rational thought and therefore must be controlled. (BTW this is a gross oversimplification but hey it’s the day before Thanksgiving.)

The parasite in the pig, the body-controlling helmet, the crowd of adults and children watching lifeless bodies jump on command, and the massive blob that destroys the lab at the end of the game all mess with the symbolic order of being/non-being in some way, particularly in bodily autonomy. Each example raises questions about who is actually controlling the bodies. Are we the player controlling the boy, or is he convincing us that we are controlling him? Is the boy just as bad as the villainous authoritarian leaders when he controls others’ bodies for his own progress? Is the parasite of the pig inherently bad, or is it simply reanimating an already-dead entity? And what is that blob doing when it rolls down the final hill toward some kind of freedom?

Also why do none of these characters have faces?! Can we truly even call them characters, humans, or beings?

I’m going to come up with some answers eventually, but for now, I’ve just got the energy to raise them, just like that poor little pig.

I know that Inside is a unique experience in these terms, but in general I find less of a disconnect with the boy and more of that I embody them. I’m role playing as them. That act of role playing is complicated, as you note, by the lack of any obvious goal or motivation. Still, progression and survival are goals in their own right. To move from left to right, to discover, is in its own way a motivating force, for both me the player and me the character.

Your analysis kind of reminds me of Pac-Man (because I watched Tim Rogers amazing review of it this week) in which the only “flavors” as Tim Rogers puts it are “Hunt” and “Be Hunted.” It feels like in Inside those are the two flavors as well, when destroying the lab you have flipped that switch. I wonder how many action games can be boiled down to those two modes of play. In Pac-Man there is no narrative either. Games like this always make me feel (as the perpetual role-player) that its my job to fill in the gaps. Part of me feels like your questions here are almost a refusal to unconsciously fill in the gaps, which is an exciting way to think about games scholarship in general.

Erik, these are great comments! I’m thinking that what Inside might do differently than something like a Pac-Man is that it seems to make the relationship between the player and the character more complicated. I like the idea of the player being a role-player, assuming the role of a character, but I think thematically there’s a lot of people who aren’t in control of their bodies in the game, for a variety of reasons. There’s also a secret ending to Inside, where the boy you’re playing as crosses paths with a man hooked up to a helmet in front of a computer. You, as a boy, pull the plug from the computer, which makes the boy’s body go limp, implying that the boy is actually being controlled by this man in front of the computer, who I think is supposed to be you as the player. I wonder if there’s something fruitful in thinking of you as the player as a parasite, which isn’t necessarily a negative entity, although it can be. What I like about bringing the concept of objection into the game is that the abject is something beyond the symbolic order, which disturbs our understanding of those fundamental dichotomies we base our existence around. And positioning the player as a parasite, or a mind-controller, while also allowing the boy some agency beyond the input of the player, really messes with those dichotomies of player/character.