Just a little background: I’m new to the group and I’ve only been part of three Lunch Zones at this point. So I won’t be talking about streaming as part of Serious Play, but rather about me and my friends making fart jokes over the internet. And maybe some reflections about the necessity of history, connection, and play in these days where physical proximity is severely limited.

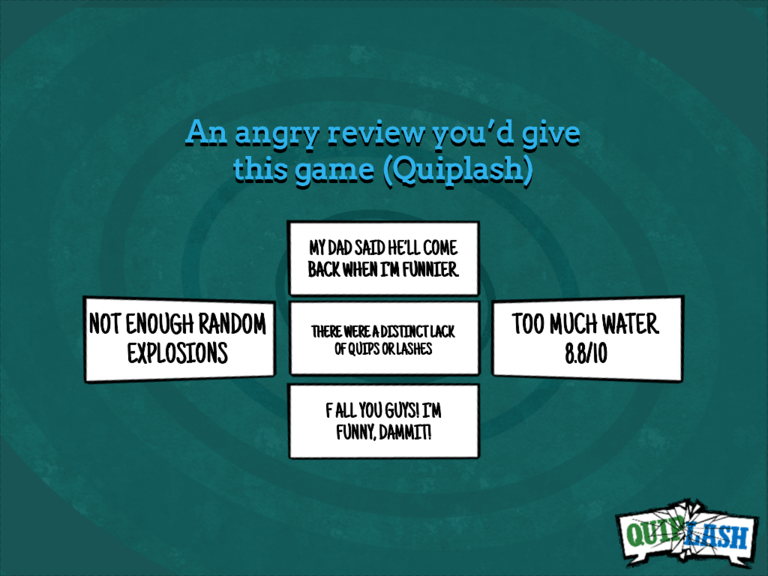

Quiplash (2015) is a weird game to write about for a group dedicated to streaming games. In the game, 3-8 people spend three rounds answering prompts like “A better name for France” on their phone. The answers for these prompts then show up on the main laptop or TV screen that everyone can see. The game pits two player’s answers against each other and the audience gets to vote for the best, often funniest, one. Of course, inside jokes and double entendres abound in a game like this.

(This is not a screenshot from a game I’ve played with my friends, because ours would make 10x less sense than this to any normal human being.)

First, let me just say how emotionally gratifying it was to jerry-rig a setup of a variety of TV and laptop screens so my friends and I could play Quiplash last night. My friend Eli who is in South Korea video called a group of us over Facebook messenger and pointed his laptop at his TV which had the game on it. My other friend Katy was videoing in from her janky laptop and the camera kept constantly glitching, making her look like a character right out of Unfriended (2014). You know, the movie about haunted Facebook? Although our setup was more than suspect, we played three rounds of Quiplash, each answer coming in worse, but somehow better, than the one before. It was loud, it was crass, and it was all around stupid, but it meant so much to hear my friends laughing with me again.

Party games like Quiplash are some of the best weapons against the socially distanced lives we’re living right now. These game encourage, and often require, players to know each others’ sense of humor and shared histories. To win a game like Quiplash you have to know what the others players would respond positively to and referencing some old story back from high school almost certainly makes any answer a shoo-in for winner. The affective connections we’ve built over the past fifteen years play out across our screens as we try our best just to make each other laugh. In days where it often feels like we’re all alone, getting together to be silly with one another takes us back to happy memories and creates new stupid phrases for us to share with each other in the future. If we think of play as a magic circle or something that takes us out of daily life into a different aura of experience, games like Quiplash really provide the opportunity for friends to explore their shared pasts, all couched in potty humor.

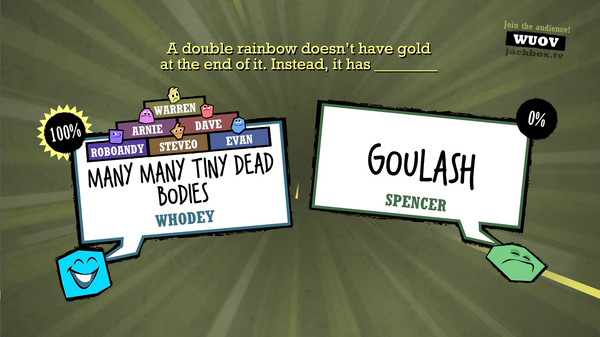

(Most games feature some kind of inside joke, like this reference to IGN’s infamous review of a Pokemon game that claimed there was too much water to surf on, which I actually kind of agree with. Again, not a screenshot from my game.)

Bringing it back to Serious Play, Quiplash seems to be the exact opposite of a game I would want to stream to an audience outside of my immediate friend group. Who else really cares about a reference to a crush my friend had back in high school? Or about the ways we have always made stupid rhyming words? Or the debate about where exactly the term “cornholio” came from? (Somehow all of us know the term even though we’ve never seen Beavis and Butt-Head (1992).)

But party games like this are wildly popular on game streaming sites. Gamers on YouTube have millions of hits on videos featuring Quiplash gameplay. In an industry that rewards individuals for their (often carefully constructed) acts of disclosure, it makes sense that people would want to see how their favorite personalities would interact in a game like Quiplash, where inside jokes let the viewers feel even more intimate with the players on screen.

Yet to say this longing for intimacy with cultural producers is a recent phenomenon ignores the ways media products have encouraged people to feel like they’re in on the story or the joke for centuries. Jonathon Swift’s A Modest Proposal (1729) and so much satire depends on the reader understanding the conventions the writer is critiquing and messing with. The reader has to be in on the joke, fostering a kind of affective connection. Magazines from the early era of Hollywood promised access to movie stars’ lives and their secrets for success. And many cultural products, like RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009), establish their sense of humor through references to other media products, further enmeshing the TV show with the audience’s previous pop cultural knowledge and personal history.

(The only way to understand this meme is to know all of its parts, from the schlocky love poem format to the reference to Beyonce’s former music group to the gay community’s historical use of puns.)

So what does all this matter to streaming games and my friends and I playing Quiplash? In an extremely broad sense, watching others play games exemplifies all the ways our media and cultural products are designed to encourage affective connections with the audience. We might have different reasons to stream, but we often stream to interact with other people. We play party games to foster and remember our emotional histories. We all want to be in on the joke. At a time where people are really hurting, the future is scary, and we’re unsure of what we’re going to do day to day, simple humor designed to bring people together is one major way we can maintain and even rebuild the affective connections that we’re faced with losing.