On this week’s episode of The Arena, Erik, Kelly, and I discussed wonky character design, the failures of multinational corporations, and the phenomenon of using Twitch as a marketing platform. If this doesn’t quite make it clear: on this week’s episode of The Arena, I played Valorant while we talked about how unsurprisingly disappointed (at best? I don’t think I can quite explain Erik’s rightful and fervent dislike of Riot Games as a company and employer) we were by Riot’s latest mash-up. You can watch the episode here.

I want to start this off with a disclaimer: Monday’s stream was the second time I have ever played a Riot game. The first time was Sunday night, when I panic-played the game after realizing that the stream was the next afternoon and I hadn’t even installed the game yet, let alone tried the controls. This was mostly, admittedly, because Riot games never interested me. I didn’t know much about Riot games’ questionable practices and the wide-ranging discourse about the company circulating within the gaming community. Luckily, this LA Times article from late 2019 sums it up quite nicely.

In spite of the disclaimer, this blog post isn’t about Riot games as a company. This post is a form of follow-up, I suppose, to my last post about first-person shooters. Whereas last time around I delved into the shooter genre writ large and began to ask/answer some preliminary questions about reading the genre in its context, my aim here is to first talk a bit about the way Riot used Twitch to market and stress test Valorant, then share what it’s like to actually play the game.

Topping the Twitch charts (just like they knew they would)

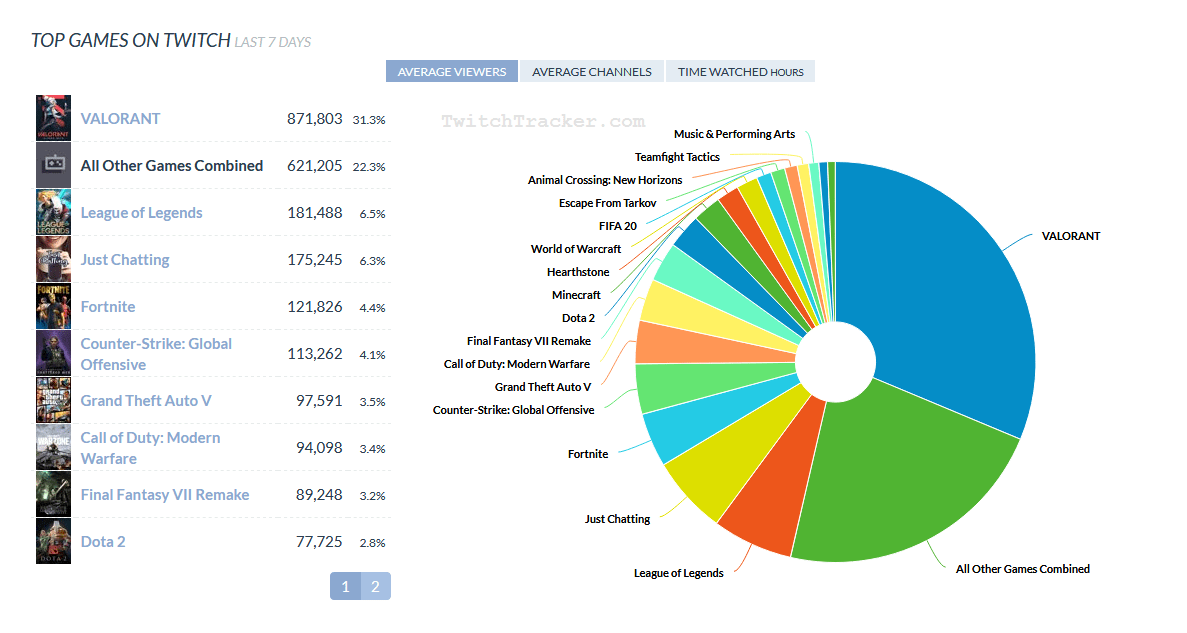

About three weeks ago, I read an article from Dot eSports about reserving your Valorant username before the closed beta was released. At first, that made no sense. Honestly, I felt weary from yet another round of hype culminating in a vague spirit of “you’ll never believe how groundbreaking this shooter is, it’ll change everything!” Undoubtedly, it wouldn’t. However, Riot certainly pushed marketing as though it would. In early April, Riot enabled drops on certain streamers’ broadcasts that would grant random spectators access to the closed beta. In the last week alone, Valorant accrued an average of just under 872,000 viewers (TwitchTracker). To clarify, the game isn’t released. It’s not even in an open beta. The closed beta opened to the public through random drops promised to those diligent about watching Valorant streams from content creators like Pokimane, TimtheTatMan, Summit1G, and others. In other words, a game that hasn’t been released has dominated Twitch viewership since the developer’s decision to release grant access to the game’s beta in exchange for an indeterminable number of hours spent watching Twitch streams. During the stream, Erik perfectly described what I saw Riot doing as “creating scarcity.” He’s absolutely right. Erik also pointed out that those primarily losing out are advertisers on Twitch, considering that people (like myself) had a number of streams open at once and would leave these broadcasts sit idly for hours in the hopes of acquiring a code.

TwitchTracker’s reporting of the top games on Twitch ranked by the average number of viewers over the last seven days. Valorant, currently in a closed beta stage, holds 31.3% of total viewership on the platform. (TwitchTracker)

By creating artificial scarcity, Riot drew incomparable attention to their new game. Since the closed beta’s opening up (yes, I see the irony) to the Twitch viewing public, Riot has progressively increased the cap of players allowed into the beta. As we discussed on stream, this is, again, primarily a problem for advertisers dumping money into ads that only reach an empty room. It also exposes the poorly kept secret about Twitch’s inflated viewership.

What it’s like to actually play Valorant

So, while I have never played a Riot game and only have a handful of hours playing Valorant, I do have experience playing Overwatch. However, I don’t have much experience with Counter Strike. If you’re unfamiliar with Valorant, using Counter Strike and Overwatch to talk about Valorant might feel like it’s out of left field. However, as we discussed on stream and as numerous outlets like PCGamesN and have pointed out, Valorant feels and plays very much like someone who enjoyed Overwatch’s emphasis on diverse hero abilities and team play really wanted to play Counter Strike instead. It’s worth noting that as a mash-up of two different games, Valorant itself lacks the unity that make both CS and Overwatch competitive eSports titles. Significantly drawing from CS, each round of Valorant (an, in my opinion, unbearable 40-minute commitment) pits two teams of five players against one another in a closed map with one of two objectives: (1) plant an explosive or (2) prevent the opposing team from planting the explosive and, in the event of failing to do that, defusing the explosive. The alternative win condition for both teams is to eliminate all enemies. Moreover, Valorant’s weapons, mobility (watch your corners), and map design overtly draw from CS, as Erik explains earlier in the stream. The game’s abilities and characters clearly emulate Overwatch’s hero and class system, but the characters’ special abilities don’t quite work cohesively or encourage players to operate as a team in the way Overwatch’s heroes do.

While I played through different characters I unlocked through my slow progression in the game, Erik read characters’ abilities and we talked about the lack of cohesion between characters in what is purported to be a team-based game. Healers that create barriers and obstructions that inhibit opponents’ mobility, characters with four slightly different explosive devices, and frustratingly similar (though with less logical and coordinated abilities) copies of Overwatch’s Reaper and Hanzo really only scratch the surface of some of Riot’s stranger choices for Valorant. Riot’s supposed “Overwatch killer” plays like a needlessly complicated round of CS with Overwatch-like “skins” and environment design. Characters’ abilities generally fall into four categories (1) small explosives, (2) barriers/obstructions, (3) mobility, (4) this smokescreen that everyone has but each character’s smoke is a different color.

- Hanzo, a hero from Blizzard’s team-based first-person shooter Overwatch.

- Sova, a hero from Riot Games’s new first-person shooter, Valorant.

In all, the value of Valorant is not so much in its contribution as a game, but rather as an example of ways to exploit the developer-player-spectator-streamer relationship that manifests on live streaming platforms like Twitch. This game and the discourse surrounding it furthers the discussion about the train of shooters releasing in beta, openly testing the game with the public, developing a community, and eventually (1) staying in beta forever, (2) moving to a full-release F2P title, or (3) transitioning to a paid full-release. In several cases, Valorant apparently being one of them, professional players and teams emerge before the game’s full release. What does this pipeline of game production suggest for other titles and genres? The “closed” beta phenomenon often occurs with shooters, battle royales, or other competitive conflict-driven titles, which makes me wonder about how games in other genres (perhaps with other purposes) relate to their communities differently.