Source: The material below was taken verbatim on 30 September 2013 from an archived version (dated 8 March 2012) of a sequence of web pages by Andy Goddard that are no longer available. The archived URL is given for each segment. I have deleted several obsolete links and comments that were in the original text; these deletions are noted with ellipses in square brackets [. . .]. Martha Carlin, 30 September 2013.

Introduction [http://web.archive.org/web/20120308184841/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing01.html]:

The clothing I make and wear as a Medieval re-enactor is, for many modern viewers, the most obvious difference between these two cultures seperated as they are by seven and a half centuries. Many suppose that as it’s so different to modern clothing it can be neither comfortable nor practical. Well, it’s time for the truth! The clothing works – we probably shouldn’t be suprised that it does – and, as Dedicated Practical Experimental Archaeologists (who incidentally enjoy nothing more than feasting and fighting in the woods) at the end of an event or a weekend it is always a slight shock to return to the constrictions presented by my modern clothes.

Obviously all our work depends on reliable, datable, evidence from a range of trustworthy sources. One extremely valuable source (the well-known Macieowski Bible) details in plate after plate a huge variety of items related to both contemporary military campaigning and home life. The quality of this work has led – over the last few years – to some members of Circa:1265 recreating clothing and items from this Bible’s crisp and outstanding illustrations.

These webpages are a brief overview to standard male clothing worn by all members of society and specifically to the extra layers and armour worn by the most well-off knights of the middle of the 13th century. Armour is evolving rapidly throughout this period and some information has been included regarding the direction that this evolution is taking.

Drawings have been used to keep the image file sizes low, and to help illustrate the points involved. [. . .]

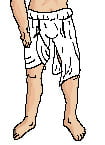

Braies [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005170244/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing02.html]:

These are the lowest layer of clothing worn by people of this century. They are large, baggy drawers made from linen and they seem to be worn by men from all classes of society under their normal clothing. We know what they look like from well-documented illumination examples of hot field-workers dispensing with all their clothes other than their braies for both modesty and coolness.

The look can be recreated with approximately 100″ of 30″-wide fine linen. Simply make a pair of shorts far wider than you can possibly imagine, and incorporate a roll at the top to contain a drawstring. The excess material (almost three times the actual waist line) is bundled up all around the body. The drawstring roll requires two slits for attaching the hose (leggings) at the front.

The inside of each leg is slit virtually up to the crotch so that the mass of material here can be overlapped neatly under the hose without creasing. This slit also enables gentlemen “normal functionality” whilst standing. When braies are worn without hose, the front corner of the leg cloth is often shown wrapped around behind the leg and tied up to the hose tie as demonstrated by our knight’s right leg. This is a handy way of dealing with all the cloth involved.

In use, the braies are suprisingly cool and comfortable, if not a little “airy” and (ahem!) “freer” than underwear that we’ve got used to in the 20th Century. Putting them on takes a couple of minutes, and the only drawback I’ve found is whilst sleeping in them – the material tends to lag as you roll over during the night. The rolled up waistband is deeply unattractive to modern eyes, but is an almost essential item when chausses are being worn.

[. . .]

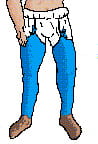

Hose [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005163631/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing03.html]:

Tight-fitting hose are the leg coverings for men throughout the Middle Ages. These are never “trousers” – they are separate leggings for each leg. Normally made of wool, they are best cut “on the diagonal” across the warp and weft as this increases their springiness and elasticity but admittedly it isn’t a very efficient method of construction. Unfortunately, no modern made hose using this type of cut quite equal the tightness clearly shown in original illuminations. Do these illustrations therefore reflect an ideal, or are we missing something? One line of thought suggests that some stitching may have occured at the ankle once the hose were on, though it would seem an unlikely thing to do for the poorest in society.

Some hose stopped at the ankle, while others incorporated feet. A variety of colours were used, although generally each leg was the same colour. For women, there is evidence of stripey hose (running horizontally), and further evidence suggests that women’s hose may have stopped at the knee and have been held up with a tie under the knee. All mens’ hose have a front tie at the top, and for appearance seams are best made at the back.

Over his hose our knight is wearing leather ankle boots. He’s dressing to fight as a mounted knight, so the quality of these with regard to walking comfortably isn’t a great issue. As a re-enactors I wear authentic shoes, and it takes some time to get used to walking about without treads, thick soles and heels to help me.

Chausses [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005165657/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing04.html]:

Our mounted knight fights with the best protection that is available for our period, and full mail hose (known as chausses) are worn. These are a development of an earlier form that just protected the front of the leg, being tied with long laces all the way up the back. These full mail chausses are heavy items, and the nature of mail means that they need a lot of support. To that end, they tie off to a stout belt which rests on the roll at the top of the braies: this is adequate enough to take the weight of the thigh armour. The knee needs to flex, however, so further tight ties around the leg below the knee support the mail on the calfs and also provide a small “bag” of mail for movement at the knee.

These chausses also cover the feet. To be able to put them on over the heel, there is an amount of mail that can’t tightly follow the skin at the ankle. Again, the illuminations never show this on armoured men, but fortunately spurs help to hold the mail together at this point. Possibly this is another illustrative short cut, but it might also suggest that mail is slit and has a short lacing behind or beside the inner ankle.

Similarly we don’t know what happens below the foot – it is unlikely that a mail sole was used – so adopting what occurs on the palms of the hauberk makes sense and as a result the mail at the edge of the foot was possibly stitched to a leather sole.

The chausses I’ve made weigh about 6 kilogrammes each and, like some pictured examples, don’t have these integral feet. Once tied on firmly (and this is essential in order to ensure that the mail moves with the leg) they are relatively unnoticeable. They limit leg flexibility only a little bit – certainly not enough to prevent me running up or down steps, for example.

Cuisses [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005165518/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing05.html]:

The final leg protection is present in the form of a pair of cuisses. This cloth armour is made by stuffing a double layer of linen with a variety of substances: horse hair, rope pickings and even straw are known. The stuffing is kept in place by quilting through the structure, and the final result is an excellent, light (if hot) method of spreading the force of a blow over a wider area to reduce damage. Like the chausses, each cuisse is tied to the belt to keep it at the right height.

For a knight on a horse in a normal riding position (with legs more extended and forward pointing than on current saddles: more “Harley Davidson” than “Japanese Rice Rocket”) it’s likely that the cuisses could be a relatively tight fit over the chausses – this lack of movement in the cuisse allows the vulnerable kneecaps more guaranteed protection in the form of extra armour. This is provided by a pair of poleyns – virtually the first use of plate armour used on the body. Initially, as here, these are little more than beaten domes of steel stitched to the cuisses, but they quickly develop into more complex forms protecting the whole knee joint from side attacks.

This picture also shows the early form of prick-spur worn on the feet. Short rowel-spurs (rotating spiked wheels on the back of spurs) are first introduced in around 1280 in England, but these prick-spurs have developed the relatively new curved support that ensures they run under the ankle bones, a development from the flat support that arrived with the Norman invasion.

Gambeson [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164005/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing07.html]:

While the upper protection offered by mail is an excellent form of armour against cuts and thrusts, it offers no protection against direct blows to the body. Similarly, individual links can be torn out of a mail coat and driven deeply into wounds with a consequently high risk of infection. As a result of this, some sort of protective layer was required to dilute the force of blows by spreading them over a wider area.

By the middle of the 13th century, padded armours like the cuisses had been fully developed and these were widely used on various parts of the body. This knight is wearing a gambeson which will be covered in mail, while the lesser ranks of foot-soldier would use them as their only form of protection in battle.

The gambeson is sometimes also referred to as an aketon, but there seems to be no reason for differentiating between the terms. The gambeson, like the cuisses, is padded and made from either linen or wool (the word “aketon” derives from Arabic and suggests the use of cotton). As mentioned earlier, generally the quilting ran vertically.

Not suprisingly, gambesons varied in many ways. Often they were left a natural linen colour, but there is plenty of evidence for coloured ones, and this one has been dyed a rich russet colour of a type that sometimes appears in illuminated manuscripts. Some gambesons had integral mittens, while others had no arms at all and were just worn as chest protection. Quite often, footsoldiers would wear more than one gambeson on top of another for extra protection, albeit at the disadvantage of less manouevreability. Evidence of dagging (that is, the tongues of fabric around the bottom of this one) is also occasionally seen.

Gambeson [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164307/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing08.html (text) and http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164319im_/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/images/gambeson.gif (photo)]:

This is my old primary under-mail gambeson, and it was machine-sewn. My current gambeson developed from this one and was hand-sewn throughout.

For this gambeson, the padding was reduced slightly at the arms to allow more flexibility, and unlike the drawn gambeson on the previous page this one has a short slit at the front to allow more leg movement. It’s not obvious in this picture, but this gambeson also has thumb straps stitched into the sleeve ends and back of the neck: this helps prevent the sleeves riding up the arms as the mail is put on, and the neck loop helps pull off the garment.

My new gambeson is made from a light brown, pure linen, and was hand-stitched using wool and linen threads. Linen threads were used for the cloth, hems and joints, the wool for the quilting. It was a slow process – I took about half an hour per quilt run – but I got a much better “quilting control” during manufacture than I ever could with the sewing machine. The new gambeson is slightly longer than this one, to go with my new, full-length hauberk, and it has an undagged lower edge, along with a tightish integral collar with a lacing up the side of the neck. The collar provides protection for my neck under the hauberk, and it doesn’t interfere with my use of a heaume. It’s also good at keeping the sweat off my mail, though I am finding my hauberk rusting at the neck and wrists.

[ . . . ]

Hauberk [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005165731/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing09.html]:

The principal armour for the torso and arms during this period is the hauberk. Like all mail, this was made out of thousands of steel links, each overlapped and rivetted, and each generally connected to four other links.

My hauberk includes mittens and as suggested earlier the palms of these mittens are leather and are stitched to the surrounding mail. The centre of these palms are slit, and this is an authentic method of enabling the hands to be freed to do intricate work. While fine linen gloves are known from sources dating from the mid 1250’s, mail gloves (with individual fingers) are a later invention, first seen from around 1300.

The head is covered by a mail hood which is directly attached to the hauberk. Slightly later periods clearly show seperate mail hoods, but these would appear to be unusual in our era. This hood (which is shown in place in the next picture) rests on the padded coif. A tie above the brow helps hold the mail coif in position, and the throat slit, which enables the mail to be thrown back, is doubly protected by the presence of an aventail which covers the chin and rises up to be tied to the browband.

For further head protection under the final layer provided by the heaume, there are examples of metal skullcaps worn between the coif and mail, called cervellieres.

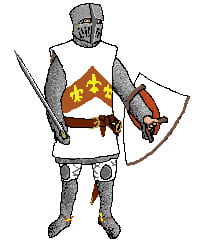

Final body armour [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164213/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing10.html]:

New for our period is the presence of the second major piece of sheet steel armour for the body. This coat-of-plates consists of flat pieces of steel stitched behind a leather or canvas covering. It may very well be a development of a cuir-bouilli (boiled leather) torso protection that proceeded it, but the presence of a surcotte on almost all illustrations makes accurate analysis difficult.

The coat-of-plates fits tightly over the underlying layers, and evidence from slightly later battlefield graves shows a variety of styles: some have plates running vertically, some horizontally, some tie at the back and some are put on poncho-like and tie at the sides.

My coat-of-plates weighs about 7kg and is remarkably effective in spreading the force of concentrated blows (like those from a sword or spear) over a large area of mail and then onto the gambeson below. Indeed, under controlled and safe conditions, blows of a startling intensity, that would easily fracture unarmoured ribs from our blunt-edged weapons, result in little more than a slight stagger.

This knight also carrys a heater shield on his left arm. This is a shortened form of the standard foot-soldiers’ shield of our period and it is particularly suited to using whilst on horseback (as the vulnerable legs are nearer to the arms). The shield is a gently curved construction of wooden planks. The edges might be strengthened with rawhide and the front surface was often laminated with canvas or thin leather before the heraldic devices (which are hidden at this angle) were applied. Two straps firmly hold the shield to the arm, and a padded support on the back of the shield softens blows that might otherwise damage the forearm. A guige (long strap) is not shown.

Final layer [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164401/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing11.html]:

Our knight is wearing a rivetted steel heaume, or great helm, that is datable to a decade or so each side of 1250. It has a slightly curved top, but doesn’t offer the “glancing faces” and increased protection that the slightly later “sugar-loaf” helms offer. The front of the heaume is reinforced with thicker steel strips in the form of a cross. This cross, and its ends, were often decorated or shaped to add interest to the heaume. The whole lot sits solidly on the mail coif, although sometimes it was kept in place by the use of an arming cap, which was a roll of cloth (often part of the padded coif) which accurately and securely located it.

There is some evidence that crests may have been worn on top of heaumes at this point, these would generally have been simple devices denoting the wearer and not the elaborate crests seen in tournaments and later periods.

My heaume weighs about 3kg, and was hand rivetted from curved steel plates – there are no compound curves and complicated beating was not required during its construction. As expected vision is very limited. The presence of ventilation holes in the face guard not only allows some fresh air in, but partly offsets the vision handicap by offering some idea of what is happening directly in front of the wearer.

The body armour is now covered by a surcotte. Heraldry is rarely shown on surcottes of the 1260’s, so this knight is wearing Sir John Peyvre’s coat-of-arms from the late 1200’s.

[Conclusion] [http://web.archive.org/web/20111005164903/http://www.bumply.com/Medieval/clothing12.html]:

Finally, the sword carried (for use after breaking or losing a lance on horseback) is a typical sword for the period; it’s about 90cm long, double edged with a central fuller and quite unbalanced. Loss of this primary weapon in the thick of combat must have been a widespread fear, and German knights in particular developed a fondness for chaining these (and their heaumes) to their bodies.

The armour at this point masses some 32 kg, a figure disturbingly close to the classical “70lb” of infantry men throughout the ages. In itself, this isn’t an improbable loading especially as this mass is closely connected to the body and is thus well-distributed. The major drawback for the novice wearer is that the centre of gravity is noticeably higher than in a normal clothed state.

To avoid problems when fighting on foot, this unusual state of balance coupled with the use of authentic footwear requires care and experience in a variety of conditions. However, all this extra mass is an advantage in the push and shove of shield-wall fighting.

One disadvantage I’ve found is that if knocked down onto my back whilst wearing all the above, the reduced torso flexibility makes it virtually impossible to sit up – you have to (vulnerably) roll over onto your knees and elbows in order to stand again. Still, you would be unlikely to be killed once the ground: a knight would be worth ransoming, compared to the average infantryman. This may be one of the reasons why we see a trend towards greater ostentation and heraldic display through the 13th century, along with the appearance of aillettes, such as those depicted above. In practice, I’ve noticed in the fury of fighting alongside people, it is easy to lose where you are, relative to others. Things move quickly, and the very real fog of war confuses things. Therefore wearing advertising hoardings such as these, fighting under a banner, and drawing on battle-cries pertinent to your family may have been extra ways to ensure you and your retinue stayed together and fought together in the heat of battle.